Virtuosity and Performance

Mastery issue, 2003/04

Virtuosity and Performance

Mastery issue, 2003/04

Researching Lègong: somatising Balinese ideas of bodily discipline, mastery and virtuosity in a non-Balinese context

Copyright © Alessandra Lopez y Royo and Ni Madé Pujawati 2003.

(No part of this text may be reproduced without the written permission of the authors.)

This material was presented live at the

Virtuosity and

Performance Mastery symposium for postgraduate/research degree students and academic

staff over two days by Performing Arts at Middlesex University on 31st May and 1st June

2003.

This material was presented live at the

Virtuosity and

Performance Mastery symposium for postgraduate/research degree students and academic

staff over two days by Performing Arts at Middlesex University on 31st May and 1st June

2003.

Practice-as-research is what best

describes the work that Ni Madé and I have been doing since last December. This

presentation will encapsulate our overall approach, combining elements of demonstration (the

teaching process and the dialogue between dancer-researcher/dancer-teacher) and will be

informed by two of our main research questions:

Practice-as-research is what best

describes the work that Ni Madé and I have been doing since last December. This

presentation will encapsulate our overall approach, combining elements of demonstration (the

teaching process and the dialogue between dancer-researcher/dancer-teacher) and will be

informed by two of our main research questions:

1. How Lègong dance is taught and a particular somatisation of bodily discipline, encompassing ideas of femininity, is achieved through learning the dance (I use here the term somatisation instead of the more usual 'embodiment' to emphasise the physicality of this process);

2. How dancer-researcher and dance-teacher understand and explicate dance and training and the process of disciplining the body.

Due to time constraints, I shall limit myself to listing the points which through this keynote presentation we would like to address and which we can perhaps talk about in greater detail during the discussions that will take place later this afternoon.

Lègong is based on a

19th century palace dance which was originally performed by pre-pubescent girls .

It is a dance genre in the female mode. There are several Lègongs, based on

different narratives. The most popular one is the Lègong kraton or

Lègong klasik. Danced by three girls, the dance tells a story entirely through

bodily movements , in an abstract way - there is no mime as such. The dance can last up to

forty minutes in its longer version and is divided into three sections. The first one

presents the character of the condong, who introduces the two Lègongs

proper. The condong is a maid servant (though not just any servant, but one who

attends to royalty). Her dance has no specific meaning but exemplifies a type of woman, of a

particular caste and class. She moves swiftly, as befits a maidservant. Some of her movements

are drawn from the natural world, an interesting point which connects with the issue of the

process of transformation of the body, of which I shall talk presently.

Lègong is based on a

19th century palace dance which was originally performed by pre-pubescent girls .

It is a dance genre in the female mode. There are several Lègongs, based on

different narratives. The most popular one is the Lègong kraton or

Lègong klasik. Danced by three girls, the dance tells a story entirely through

bodily movements , in an abstract way - there is no mime as such. The dance can last up to

forty minutes in its longer version and is divided into three sections. The first one

presents the character of the condong, who introduces the two Lègongs

proper. The condong is a maid servant (though not just any servant, but one who

attends to royalty). Her dance has no specific meaning but exemplifies a type of woman, of a

particular caste and class. She moves swiftly, as befits a maidservant. Some of her movements

are drawn from the natural world, an interesting point which connects with the issue of the

process of transformation of the body, of which I shall talk presently.

Lègong has become indexical of Bali where dance is a commodity for global tourism and a product of the cultural industry. In outsiders' imagination Lègong epitomizes Balinese femininity, disturbingly embodied by pre-pubescent girls - this totally enraptured the Euro-American imagination for well over a century. In Euro-American accounts Lègong has become the expression of a timeless aesthetic culture and Balinese responses have contributed to these imaginings.

Balinese discourse about

Lègong is complex. Lègong is taught in internationally oriented

dance academies which define excellence and Balinese representations of their own culture are

constantly changing. Today, Lègong is regarded as the foundational dance in two

senses. First it provides the structure of dance sequences according to which most subsequent

dance is organized. Second it constitutes the repertoire of movement for dancing in the

female mode. The Balinese call it tari lepas, 'virtuoso dance'.

Balinese discourse about

Lègong is complex. Lègong is taught in internationally oriented

dance academies which define excellence and Balinese representations of their own culture are

constantly changing. Today, Lègong is regarded as the foundational dance in two

senses. First it provides the structure of dance sequences according to which most subsequent

dance is organized. Second it constitutes the repertoire of movement for dancing in the

female mode. The Balinese call it tari lepas, 'virtuoso dance'.

The body in Balinese culture is conceived as non-dualistic, body, mind and feeling are developed and transformed together through dance, a set of practices which gives mastery over dispositions in order to instantiate qualities of grace, power etc. Lègong is thus a way of disciplining this non-dualistically-conceived body, in other words, it is a set of transformative practices.

These ideas are not necessarily articulated while teaching or learning the dance, but they shape the way the practice is conceived, from which expectations arise of the kind of transformation the student's body/mind/feeling will undergo.

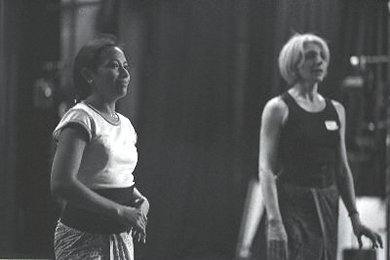

A key feature of our research

effort is that it involves an act of cultural translation. Ni Madé is Balinese, I am

not. Ni Madé was, until fairly recently, accustomed to teaching Balinese children and

adults in Bali. I am not Balinese, I am an adult, my body is scripted by gender as conceived

in a European context, by class, by race and a variety of other markers - in other words, my

body is not neutral.

A key feature of our research

effort is that it involves an act of cultural translation. Ni Madé is Balinese, I am

not. Ni Madé was, until fairly recently, accustomed to teaching Balinese children and

adults in Bali. I am not Balinese, I am an adult, my body is scripted by gender as conceived

in a European context, by class, by race and a variety of other markers - in other words, my

body is not neutral.

If Lègong is a process of mastery and transformation, through cultivation of virtuosity, the disciplining that occurs in this teaching/learning relationship has to go through a process of translation, which in turn makes the dancer/teacher question her own assumptions.

As will be seen, bodily mastery in Lègong consists in acquiring perfection of posture and flexibility. It is not however the kind of flexibility required of a gymnast, but a flexibility predicated on expressivity. It involves openness to a series of psychological attitudes whose referents are culturally specific - walking, glancing sideways, opening the eyes wide in a state of constant alertness: all these movements do not have a 'meaning' but are based on culturally learnt patterns, instantly recognizable by a Balinese. To a non-Balinese they need to be explained in terms of mechanics but also through imagery and similes designed to enable achievement of an ease of execution, with the desired aesthetic quality.

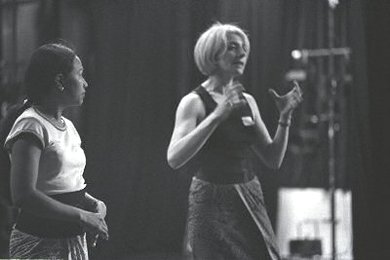

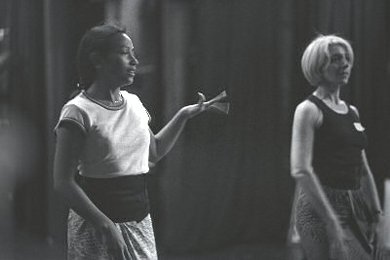

This will suffice by way of

introduction. In the next section of this presentation, you will see Ni Madé and myself

in a teaching/learning situation. The dance that we will be working with is the opening solo

of the Condong in the Lègong kraton. I should clarify that this is not

a demonstration of Lègong, therefore there will be no specific explanations

directed at the audience: what you need to observe is the dialogue that will take place

between myself and Ni Madé . A dialogue, I should point out, which will not necessarily

be verbally articulated but will often only involve our bodies in a discursive framework

where they will mutually respond to each other, in the process of dance creation.

This will suffice by way of

introduction. In the next section of this presentation, you will see Ni Madé and myself

in a teaching/learning situation. The dance that we will be working with is the opening solo

of the Condong in the Lègong kraton. I should clarify that this is not

a demonstration of Lègong, therefore there will be no specific explanations

directed at the audience: what you need to observe is the dialogue that will take place

between myself and Ni Madé . A dialogue, I should point out, which will not necessarily

be verbally articulated but will often only involve our bodies in a discursive framework

where they will mutually respond to each other, in the process of dance creation.

[At this point in the presentation, myself and Ni Madé demonstrated the teaching/learning situation, during which Ni Madé sang the music normally played by the gamelan. Following this the audience was invited to participate, asking Ni Madé questions about the dance and the teaching. Then Ni Madé demonstrated her mastery of Lègong, by dancing the role of condong, with full musical accompaniment recorded on a CD)

Conclusion

Throughout the presentation a number

of interrelated issues have been addressed and questions raised. Among these were

disciplinary mastery and how this relates to research; the understanding of that disciplinary

mastery in a trans-cultural context; practice as research and conversely, research as

practice. The whole presentation was a particular kind of performance, which in terms of

evaluation would have to be considered primarily for its research worthiness, rather than its

aesthetic impact as performance with the exception of the section which demonstrated the

dancer's mastery. One of the questions this symposium addresses is: do we need to be able

to write differently when the major focus of research is creative practice? Our answer is

that indeed we do. In our case, much of the dialogue and research occurred and occurs through

'bodily writing'. We therefore need to consider different ways of writing up research

in the creative and performing arts, through a variety of media. We acknowledge that there is

a difference between performance as performance and performance as research - framed by

specific research questions - but that more traditional academic writing cannot always do

justice to this mode of enquiry. In this Lègong project, the research knowledge

generated is somatised; this would be difficult to explicate without engaging in 'bodily

writing'. We are not implying that one cannot research and write about

Lègong in other modes; but when we consider the process of somatisation the

knowledge produced cannot separate body from mind and needs to be articulated as 'bodily

writing'.

Throughout the presentation a number

of interrelated issues have been addressed and questions raised. Among these were

disciplinary mastery and how this relates to research; the understanding of that disciplinary

mastery in a trans-cultural context; practice as research and conversely, research as

practice. The whole presentation was a particular kind of performance, which in terms of

evaluation would have to be considered primarily for its research worthiness, rather than its

aesthetic impact as performance with the exception of the section which demonstrated the

dancer's mastery. One of the questions this symposium addresses is: do we need to be able

to write differently when the major focus of research is creative practice? Our answer is

that indeed we do. In our case, much of the dialogue and research occurred and occurs through

'bodily writing'. We therefore need to consider different ways of writing up research

in the creative and performing arts, through a variety of media. We acknowledge that there is

a difference between performance as performance and performance as research - framed by

specific research questions - but that more traditional academic writing cannot always do

justice to this mode of enquiry. In this Lègong project, the research knowledge

generated is somatised; this would be difficult to explicate without engaging in 'bodily

writing'. We are not implying that one cannot research and write about

Lègong in other modes; but when we consider the process of somatisation the

knowledge produced cannot separate body from mind and needs to be articulated as 'bodily

writing'.

Alessandra Lopez y Royohas a PhD from SOAS, University of London and lectures in Dance Theory and History at Roehampton, University of Surrey. She is involved in research for the South Asian Dance project of the AHRB Research Centre for Cross-cultural Music and Dance (SOAS, Roehampton and UniS) working on Odissi and co-ordinates the Centre's Indonesian dance and music heritage project. She has been working with Ni Made' Pujawati on Lègong dance since December 2002.

Ni Madé Pujawati is a graduate of the Institute of the Arts (ISI) in Bali and is recognized as a leading performer of Balinese dance-opera, Arja. She heads the London-based dance group, Lila Bhawa and is dancer-in-residence with the Balinese Gamelan Gong Kebiyar, Lilacita, and the LSO's new Gamelan Semara Dana. She is also researcher for the AHRB Research Centre's project on Indonesian dance and music heritage.

Last updated 30th August 2004.

Web design and black and white photography © John Robinson, 2003.

Video frames by Hannah Bruce and John Robinson.